At the end of every football season, the title race ends and the race for footballers’ signatures begins. ITW Core’s Devanshu Bhatt looks at the mechanics that are in motion behind the scenes and what business lessons we can glean from it.

The football transfer market is a whole brand of entertainment in and of itself, keeping the fans engaged in the otherwise eventless off season. Case in point – the recent saga involving Lionel Messi’s potential departure from lifelong club Barcelona. But while Messi eventually stayed at Barcelona, every summer hundreds of millions of dollars are spent by the top clubs in the process of recruiting the top talent. How much money clubs can spend depends on how much they earn, which in turn depends on how much they earn from Broadcasting, Ticket Sales, Sponsorship, Merchandise and Team Performance. In addition to all this, teams can also raise money by selling players.

With the coronavirus pandemic looming large, there was a feeling that this summer even the top clubs wouldn’t spend much. This has turned out to be largely true but there have been exceptions such as Chelsea, who hit by a transfer ban last summer, compensated for the lost time and spent over £130 million this summer signing three big names. Other than Chelsea, the Premier League clubs spent close to £485 million this summer, which is nearly two-thirds the £725 million spent last summer. But while these headline numbers get discusses, the real manouvering is in how these trades and deals are structured.

The Fundamentals of a Transfer

Transfers have now become extremely difficult to conduct, mostly owing to the amount of money that is involved. Any agreement that has to be made has to involve not just the clubs and the player but of late even the agent. The role of the agent existed before but has catapulted of late with super agents like Mino Raiola and Jorge Mendes. This means that signing a player requires a good relationship with the agent in addition to a hefty fee for their services. Another question that arises is how the fee is structured inclusive of bonuses, instalments etc. All of this is only part of the reason the transfer market finances become extremely complicated. One of the main reasons this complication arises is down to Accounting. To put it more simply, profits on the books don’t reflect the cash in hand at the club. At the same time, costs are not booked when money changes hands but only when they are actually incurred.

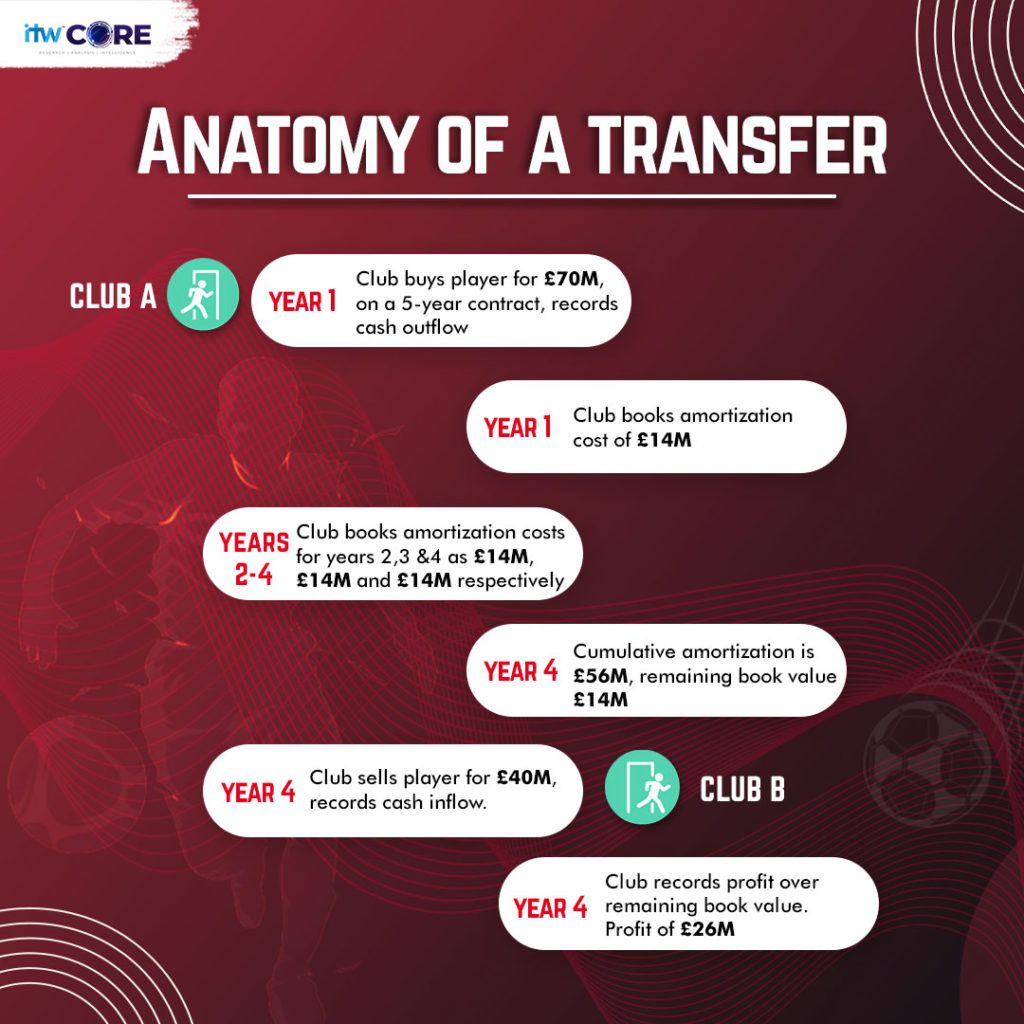

These terms can be confusing to a layperson. To make it simpler let’s break it down. Suppose a club buys a player for £70 million pounds for a 5-year contract, the cost of the player will be amortized i.e spread out over the contract length as £14 million every year. While the club has already paid the player’s previous football club the entire cost in terms of cash, they book only a fifth of that cost on their books this year. Now, suppose they sell the player at the end of the fourth year for £40 million, they would have incurred £56 million in cost prior, but since only £14 million of the value is remaining, they would make an immediate profit on their books of £26 million. Again, they receive £40 million cash in hand but record a profit that is lower. In this manner, cash in hand and profits in terms of accounting can vary. Note that while in absolute terms, the price of the player has gone down and the club has made a loss on him, due to amortization, the accounts will still show a profit.

Explaining recent phenomena

Of late we have some weird phenomena to say the least in the transfer market. A very recent example of this has to be the Arthur-Pjanic swap deal between Barcelona and Juventus. Calling it a swap deal as it has been is partly wrong. Barcelona paid €60 million for a 30-year old Pjanic and Juventus paid €72 million for then 23-year old Arthur. The difference is €12 million which is essentially the money that has changed hands, so in that sense it is a swap, but on the books, there are different implications. Many Barcelona fans wondered why their team had sold such a promising young player in exchange for a veteran in the twilight years of his career. According to Transfermarkt.com, Barcelona signed Arthur for a fee of €31 million for a 6-year contract. This translates to €5.16 million a year. By 2020, Barcelona had incurred €10.33 million of this cost. By selling him for €72 million, they make a profit on the books of about €51.33 million, and counting the money they pay for Pjanic, which comes to €15 million. This means they will show a profit of €36.33 million this year as result of the deal. Similarly, Juventus paid €32 million for 5 years which is €6.4 million a year. By selling him for €60 million they are net positive by €53.6 million and counting the money they’ll pay for Arthur, which is €14.4 million, they also show a profit of €39.2 million. So, the overly inflated transfer fees basically enable both clubs to show profits in excess of €35 million. This allows them to simultaneously balance the books ahead of Barcelona’s presidential elections and more importantly meet the 2021 Financial Fair Play (FFP) Requirements as set by UEFA.

Accounting magic, right? Of course not. No such thing. While accounting can do many things to manipulate how money is viewed on the books, it cannot save the club from its obligations. For one, despite showing €39.2 million in profits, Juventus have actually paid €12 million in cash. Secondly, in the short term , this sort of jugglery can help but it means that in the coming years, the clubs have to incur those fees in terms of player amortization. If we consider multiple players, the numbers can add up and seriously hamper the clubs’ ability to sign new players, at least without selling a few first. So, both clubs have adopted a view of fixing the now and worrying about the future problems when they arise, which could hurt them. Though with the financial might of these clubs, perhaps these problems will simply blow over within the next few years.

The Premier League Conundrum

Knowing this, we now come back to the Premier League and the case of Chelsea’s abnormally high summer spending, especially when viewed in contrast with Premier League champions Liverpool’s relatively meagre spending. Moreover, how can Chelsea spend so much money without violating Financial Fair Play Requirements? In Chelsea’s case, the simple answer is that they sold Eden Hazard last year for over £100 million and sold Alvaro Morata for another £50 million. In Hazard’s case, the player was fully amortized, meaning any money the club receives for him is pure profit. Morata had run down 3 years of his contract, leaving the club with another £26 million in profits. Being able to sign only 1 player for £8 million a year last season owing to a transfer ban, Chelsea came into this transfer window guns blazing. According to blogger Swiss Ramble, who regularly looks into club finances on Twitter, Chelsea still run on a loss. While Chelsea have generally offset player buys with player sales, having one of the highest values in terms of player sales in the Premier League, the amount they have spent on buying players is also one of the highest, meaning that the club still has an operating loss.

All this is of course helped by the fact that their Billionaire owner Roman Abramovich has regularly poured money into the club’s coffers in order to offset much of the club’s losses. The lucky thing for Chelsea is that FFP does not count all of the club’s expenses in its calculations. It excludes the academy, women’s football, stadium expenses, non-player amortization, depreciation, and community engagements as they constitute what the UEFA believes to be healthy expenditure. Despite this, Chelsea might still come out on the wrong side of the requirements. Here is where UEFA’s amended FFP requirements for COVID19 come into play. They have reduced the 2018-2020 period to just 2 years from 2018-2019. In addition, they have combined 2020 and 2021 years into a single period. This means that the 2022 monitoring will have 3 periods namely 2018, 2019 and 2020-2021. This means Chelsea still have another year to make the necessary sales to take the total loss below the limit of €30 million, where the owner will have to offset up to €25 million of the loss through an equity purchase. So, it’s very likely that Chelsea will see a handful of exits over the next year as they will seek to meet the FFP requirements, in addition to signing very few players if any over the same period. There is enough time for Chelsea to steady the ship and it isn’t panic stations just yet.

While Chelsea’s owner is more than willing to cough up the millions required to keep the club afloat, Liverpool’s American owners are not. The trend with American owners in the Premier League has been that they have treated their clubs like businesses. In the case of Manchester United’s owners have met a lot of backlash because they have bought the club against debt and also been paid out dividends. Similar discontent has been directed by Arsenal’s American owners. Liverpool fans have been left baffled by the fact that despite the club performing at the very highest level at home and abroad and also recording profits of over £175 million in the 3 seasons before this, they haven’t spent big on at least 1 or 2 players in the last 2 seasons.

This brings us back some of the ideas I alluded to before. Liverpool only has a fraction of this money in terms of cash. Moreover, a large part of profit is owing to the fact that they didn’t incur as much in terms of player amortizations as Chelsea did, in fact almost £140 million less. But since this isn’t actual cash, that sort of simplistic comparison won’t do. We also need to remember that buying and selling players is not the actual business of these clubs, thus cash is used in other places too. Clubs have debt obligations such as interest payments for stadium renovation costs etc. to pay as well. An owner might be willing to fund many operations by themselves, but a business needs to borrow money to make those payments, which depletes cash reserves. This is what I meant when I said that Liverpool is run like a business. If they want to buy more players, Liverpool will need to either sell some or need the club to inject liquidity into the club either by borrowing, loaning or simply giving the required cash to the club. (To go into the depth of the financial and accounting analysis of these clubs, you can look at the helpful Twitter threads Swiss Ramble has posted) But we must remember that the transfer market is wild and unpredictable at times and probably still has a few surprises in store. In the time that it took to write this article, Liverpool have signed 2 players.

With the kind of operations modern brands in sport are involved in, especially with the surge of money that has flowed into sports with the advent of television, they are no less complex than big businesses. Whether they are treated as such depends on the ownership. In any case, most operations with regards to player transfers depend on cash reserves and cash flow as they do for any asset acquisition at businesses. When expenditures get bigger, it gets harder to get the necessary cash to get transfers done.

It is for this reason that we see long drawn out transfers sagas with many rounds of negotiations with other lawyers or agents to sort things out. And it would not come as a surprise if we have a part 2 to the Lionel Messi saga to set up another summer of drama and entertainment, unless of course you are a Barcelona fan.